We woke this morning to a rather gloomy day. It had been raining on and off during the night. But the low clouds simply gave Okushiri Island a subdued tone, with its own beauty. Perched on the tip of the Kamuio Cape, we had great views up towards the mountains and along the coast.

[lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”false” style=”padding-left:0px”] [/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true” style=”padding-right:0px”]

[/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true” style=”padding-right:0px”] [/lgc_column]

[/lgc_column]

For much of the morning, we were meandering south along the west coast of the island. There was perhaps one car every hour or so. The official tourist sights along this stretch of the island consist of rocky outcrops jut off the beaches. The idea is that you stop, take a photo, and carry on. We duly obliged.

[lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”false” style=”padding-left: 0px”] [/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true” style=”padding-right: 0px”]

[/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true” style=”padding-right: 0px”] [/lgc_column]

[/lgc_column]

The one on the top left is the ‘grumpy-face rock’ and the one on the right is the ‘stag-beetle rock’. World famous in Okushiri Island.

And the prerequisite ‘delfie’ (double-selfie).

It really wasn’t long before we were climbing up and over the southern headland which would connect us to Aonai Village, the main fishing village and port on Okushiri Island. This involved one of the common Hokkaido snow-shelter tunnels, always good for a trippy photo.

The main event for today, however, would be the Tsunami Information center at the southern tip of Aonai Village. Situated on the low-lying cape at the end of the island, this center is the only building permitted to be standing in the area. That is, after the 1993 tsunami, the now vast parkland area – which was once densely built up with residential buildings – was designated too much of a disaster risk for dwellings. Indeed, just 5 minutes after the 7.7 magnitude earthquake, at around 10:15pm, all structures – apart from the solid concrete memorial tower – on this peninsula were destroyed by the 30m high, 500km/h wave (photo report here). The combination of a deep western seabed and a shallow ridge running southward from the peninsula, apparently makes it a prime location for any tsunami to instantly gain power, amplifying its height.

Inside the Tsunami Information center, we were given a guided tour by a survivor of the tsunami. She rattled off a speech she’d obviously given hundred of times before, but it still impacted us. She told us of how the massive wave wrapped around the southern end of the island, coming around and hitting the eastern port. All this happened within 10 minutes of the original earthquake. Residents who figured out what was going on tried to clamber up the steep bank behind the port village, hauling themselves up by grabbing onto grass and shrubs.

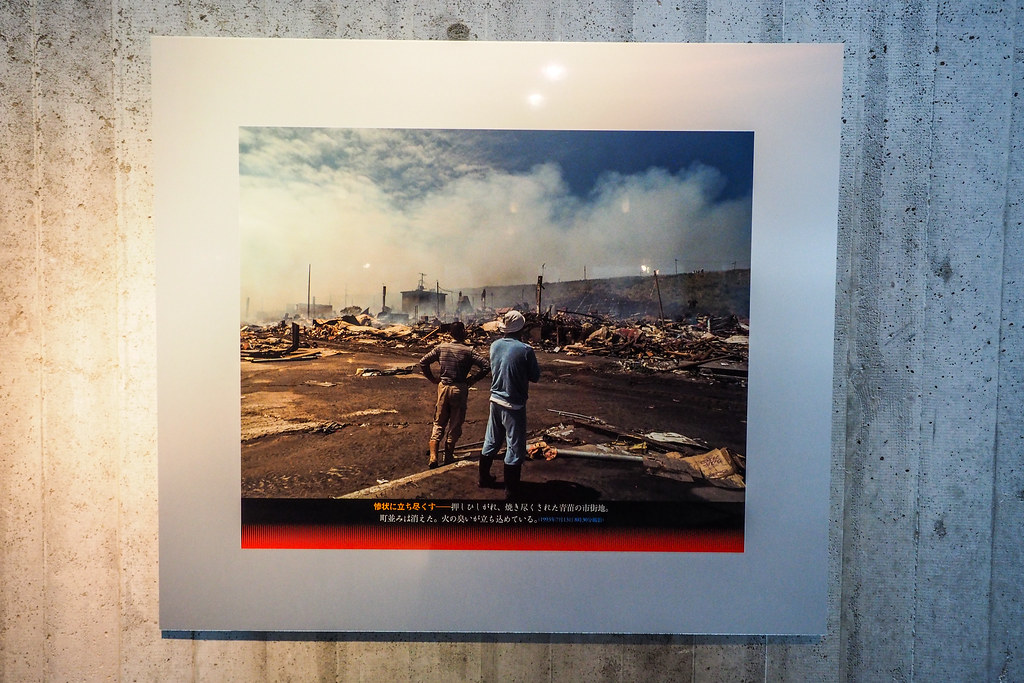

At the same time, all the fishing boats in the port, all fueled up for their early morning fishing runs, were picked up, smashed against each other, many with the fishermen still in them, trying to get them out of the port. Boat fuel tanks were ruptured, leaving a thick slick of diesel across the tsunami waves, which had now covered most of the lower-lying houses in the port area.

Then the waves subsided, leaving the entire town essentially doused in diesel. Then the fires started. Wooden structures, homes, boats, doused in flammable diesel, were now burning uncontrollably through the night and into the morning.

In this sense, there was disaster upon disaster. There were massive landslides in parts of the island, plus a tsunami, plus uncontrollable fires. Our guide said that this was the tsunami that popularized the term ‘tsunami’ in the English language. She insisted it was the one that made people aware of the possibility of sudden, massive damage by actual walls of water – not the surges we’ve become accustomed to from more recent large devastating tsunami, but 30m breaking waves.

The thing I found most fascinating at the information center, however, was a faded poster, tucked away in one corner of the entrance area. It was a poster published in 2009, indicating the probability of earthquakes in and around Japan, ranked by probability and magnitude. Most amazingly, one of the highest probability areas was just off the east coast of Miyagi. According to this poster, as of 2009, the off-shore area around Miyagi Prefecture had a 99% probability of experiencing a 7.5 Magnitude earthquake within 30 years.

Two years later the area experienced the largest earthquake in Japanese history.

After all of this reminder of how destructive mother nature can be, and how risky this southern tip of Okushiri Island was for tsunami damage, our plan of camping for the night in the large park area here was putting us both on edge. But we were not going to be alone in the park – the Japan Self Defense Force had set up camp for a few weeks for training, so we figured they must know what they’re doing (and the trusty poster above didn’t seem to think we were in danger any time soon).

Still, the experience of hearing about the disaster gave the whole place a rather sobre feel.

[lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”false” style=”padding-left: 0px”] [/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true” style=”padding-right: 0px”]

[/lgc_column][lgc_column grid=”50″ tablet_grid=”50″ mobile_grid=”50″ last=”true” style=”padding-right: 0px”] [/lgc_column]

[/lgc_column]

We made ourselves at home in the park though, and got set up for the night. The Japan Self Defence Force people kept to themselves. We took over a nice pagoda. The toilets were clean. Perfectly pleasant.

The evening treated to us an amazing sunset, and a night sky clear enough to see the Milky Way in all its glory.